Meeting Reports & Summaries

Below you will find summary reports of recent Lectures, and selected photos of Outings, from the current and previous seasons. The most recent is on the top.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the showing of a documentary film 10th April 2025)

Olive Gibbs: A Remarkable Woman

Documentary film directed by Helen Sheppard and Christopher Baines

It was a treat for us to have the two directors, Helen Sheppard and Christopher Baines, introduce the showing of this well-made film though it could, of course, very adequately speak for itself.

Not only was the film beautifully made, with a wealth of first person interviews from family, friends, local politicians, and historians, including a series of comments and reflections from Liz Woolley, but it invoked and illustrated a serious slice of twentieth-century social history.

Olive Gibbs was obviously a remarkable woman, from a very basic working-class background in the poorer part of Oxford, who got into politics in order to improve the lives of people like those she grew up with. But as the story of her life unfolded, ending up as Lord Mayor of Oxford, she got involved with a series of issues that encapsulate much of the social history of the second half of the twentieth century. Interspersed with the seaside holidays, and schools, we have the story of the Cutteslowe walls, the fight to save Christ Church meadow from having a ring road taken through it, the Aldermaston marches and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Obviously a very focussed woman, on the issues that motivated her; not perhaps a domestic goddess, nor a home-maker.

And there was much more - not just the story of one's woman's life but of all the local politics and history she lived through - put together in one intelligently made film. Well worth seeing.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the talk given on 27th Mar 2025)

The Ancient English Morris Dance

Michael Heaney

Members, together with guests from the local Morris Dance community, were treated to a lecture rich in fascinating insights into the origins, development, present and future of this uniquely English tradition. Michael Heaney is both academic researcher and Morris insider which equips him perfectly to speak as an expert on this topic. His long career at the Bodleian Library gave him access to rare documentary sources, while his membership of Eynsham Morris since its revival in 1980 kept him in close contact with the lived tradition.

Using film and music Michael ensured from the outset that his audience could distinguish between the principal styles of the Morris: Cotswold, Border and North West. Using the earliest references to Morris dancing from the 15th century he demonstrated how it started life as a high status courtly entertainment, a long way from the popular myth that it is a survival of ancient pagan fertility rites. He went on to detail its development during the 16th century as civic entertainment through association with London trade guilds and the Midsummer Watch processions; where it rubbed shoulders with processional giants, hobby horses and Robin Hood plays. Alongside this Michael illustrated the parallel development of the Morris as part of parish fundraising for the Church which led to its widespread adoption across the country.

From its heyday in the 16th and early 17th century Michael traced its gradual decline partly due to suppression by the forces of Puritanism, but ultimately by falling out of fashion. Its rediscovery and revival in the early decades of the 20th century laid the groundwork for an explosion of interest, activity and innovation in the last quarter of the century of which Michael has been an important part.

Whilst the bones of this story are familiar to many in the Morris world, Michael had much to show and say which was new in the form of little known sources and surprising details. One of the highlights was an iconic 1970s photograph of Gloucester Olde Spot Morris, a group of athletic young men, hovering in mid air above the pavement during a dance. Having seen them in action at one of the legendry Bath University Ceilidhs I can testify to the power of the Morris to excite and entertain.

Verna Wass, April 2025

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the talk given on 13th Mar 2025)

Over the Hills to Glory: the Ascott Martyrs

Carol Anderson

Carol Anderson talked to us about the Ascott Martyrs with enthusiasm and a real sense of injustice. In Spring 1873, a group of women and their children were sentenced to periods in prison with hard labour for disrupting and ridiculing scab farm labourers during industrial action in Ascott-under-Wychwood.

She started her lecture with a description of the years 1850 to 1870 as the “golden age” of British agriculture. However, the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 was finally beginning to be felt in lowered food prices, and agriculture suffered a great decline in the 1870s. This hit agricultural labourers particularly hard. Joseph Arch (farm labourer and methodist preacher) organised the Agricultural Workers Union in nearby Wellesbourne in 1872. The Criminal Law Amendment Act (1871) permitted Unions and strikes but forbade violent picketting and harrasment. Largely due to this stricture, the Union's actions in Wootton by Woodstock in 1872 were relatively ineffective; in 1873, the Union turned its attention to Manor Farm in Ascott.

The farmer of this large establishment was Robert Hambridge and Carol explained how his labourers had asked him for a rise in wages. He agreed to this, but only offered a rise to 'deserving' men. Consequently, the Union, via an organiser called Christopher Holloway, called the men out on strike, Hambridge responded by recruiting two 18 year old lads as non-union labour from a nearby village.

Carol gave great descriptions of the living conditions of the labouring families and of the impact of their extreme poverty, which directly led to a large group of Ascott women confronting the two ununionised lads during which the boys were allegedly intimidated, and something was thrown at them. The local constable was called, and several of the women were arrested, and taken before the magistrates in Chipping Norton, where 16 of them were were charged and subsequently found guilty.

Their sentences, of either seven or ten days in prison, some with hard labour, immediately became a national cause celebre triggered by the union organizer and methodist preacher Christopher Holloway writing a letter to The Times. Carol gave some great descriptions of the outrage caused by the sentences. The Home Secretary belatedly commuted the hard labour sentences of the women with children. Locally, the sentencing led to passionate demonstrations outside Oxford Gaol, and outside Chipping Norton police station - where a shout from the crowd led to the women being styled the “Ascott Martyrs”.

The women's releases were greeted with celebrations; one of the parties of women were treated to a trip around Blenheim Palace on their way back to Chipping Norton!

Carol ended her fascinating lecture by telling us how several of the martyrs subsequently emigrated. Perhaps a token of their lowly status and of the 'invisibility' of women in the 19th century and beyond was that only two of the women are known to have been photographed, despite their celebrity! Perhaps as a direct result of these events, Disraeli repealed the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act in 1875.

Steve Kilsby (March 2025)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the talk given on 13th Feb 2025)

Organisation and planning in the Mercian kingdom: a context for Anglo-Saxon Banbury

Professor John Blair

This was a fascinating lecture packed with interesting information. John Blair’s book Building Anglo Saxon England (2018) contains a radical rethinking of the Anglo Saxon world based on the latest archaeological discoveries, amongst which was a new interpretation of a feature discovered underneath Castle Quay, which none of us had heard of before. This was the catalyst which led to the invitation to Professor Blair to come to Banbury and tell us all about it.

He began by stressing the importance of the Mercian kingdom in the 8th and 9th centuries: at that period it was much bigger and more dominant than the kingdom of Wessex. We have all absorbed a history which gives Wessex the important role in our island story – but that is because we have so much more documentation from there and it is where history was written.

John Blair then told us about the theory he has formulated, that in the Mercian kingdom many settlements and buildings were laid out on a grid pattern, using a measuring rod (pole or perch) of 15 foot, and showed us various places where this could be seen, a local example being Sulgrave.

He moved on to tell us about a rethinking of what place-names can tell us about settlement patterns and organization. For some years landscape historians had been working on a ‘multiple estate’ model, but John Blair preferred to think in terms of ‘functional’ place-names – particularly tunas, which can be found in clusters all over Mercia. This is where you find Kingstons together with Charltons, Burtons, Prestons and often Newtons or Newbolds. He suggested that Kingstons possibly had a function as a kind of police station, and that Newtons, which usually had some kind of relationship with a bigger and more important place, possibly represented a transfer of administration. We look forward to the forthcoming book all about functional place-names.

What did the place-name Banbury tell us? Banna’s burh: the ‘burh’ refers to some kind of earthwork or fortification, and ‘Banna’ is probably a mythological figure, the name older than the 8th century. John Blair reminded us that a coin hoard of the Viking Age had been found in a ditch under the castle, and he showed us the plan of the possible early circular fortification laid out with a Mercian pole of 15 foot. In passing he pointed out that Great Bourton (a burhtun) was obviously a satellite of Banbury.

Deborah Hayter (Feb 2025)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the talk given on 9th Jan 2025)

Sequestration in Oxfordshire during the English Civil Wars

By Dr. Charlotte Parsonson-Young

We enjoyed a most interesting and informative talk on one of the more overlooked policies of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651); that of sequestration. Though practiced by both Royalists and Parliamentarians, Charlotte Parsonson-Young focussed her doctoral thesis and her talk on the Parliamentary policy of sequestration at a national and county level. She was able to show how the war affected far more people than just the soldiers, and notably affected women.

Sequestration was not new in 1642; it had been implemented a full half century earlier, confiscating property of non-conformists and traitors. The policy of sequestration, implemented by Parliament both during the civil wars and the Interregnum (1643 - 1660) was simultaneously a method of punishing delinquents, of cutting the resources of the King, and of funding the war efforts of Parliament. It enabled Parliament legally to confiscate the property of those who supported King Charles I, as well as all Catholics, whether or not they were actively involved in the war. The latter forfeited two thirds of their property.

To administer the process of sequestration, Parliament established, in 1643, a central Sequestration Committee in Westminster, together with 69 regional committees in towns and counties. Also in 1643, Parliament introduced a Committee for Compounding with Delinquents, allowing Royalists to compound for their sequestered estates and property. The legislation governing sequestration and compounding changed during the wars. For example, in August 1643, when dependent women (not active Royalists) were left without financial support by the sequestration of their husbands' estates they could petition (either local or central committee or both) for financial support of one fifth of their husband's estate. If a delinquent petitioned to recover an estate or property, he/she submitted a signed declaration of revenue and property to the Committee for Compounding in London. If a petition was successful a fine was paid proportional to the value of the estate and level of support for the king, often three times the net annual income, along with a pledge not to take up arms against Parliament again. Initially Parliament had planned to sell everything seized but the logistics to achieve this was overwhelming with examples of sequestrators holding onto property for over six months until buyers could be found.

For prominent Royalists, the fine could be very high, for example £10,000. Lower down the social scale (e.g. for clerks, students, apothecaries, and yeoman) the fine might be a few hundred pounds. Parliament's policy was not discriminatory by social class; if one were found to support the King one would be sequestered, although estates of the gentry were targeted as they were worth the most.

Using the five record books kept by the central Sequestration Committee in London, recording all cases referred to them and snippets about results, Dr Young’s ground breaking database of sequestration appellants has revealed the statistics of sequestration appeals for the first time, and has provided an absolute minimum number of 3,895 appellants. This figure does not consider those who petitioned locally, those who did not appeal at all but accepted their fate and those who bypassed the appeals process and went straight into compounding. It was suggested that £4.5 to £6 million was raised by sequestration but the figure could be much higher. Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, most of the sequestrated estates were returned to their pre-war owners

There are 120 record books for the Committee for Compounding of which approximately 2500 appellants have a date and location attached. This shows a movement out from the southeast as the war progressed. Oxfordshire is the one anomaly as, although authorised in 1643, no one was initially appointed to the Oxfordshire Committee; an explanation being that the city was the Royalist headquarters.

The example of Countess Lucy Downe (nee Dutton) was highlighted. Her husband's main estate was Coberley Court in Gloucestershire, though it included land at Wroxton and Wilcote. She successfully petitioned the central Sequestration Committee on being left destitute when her husband's lands had been sequestered. There is no evidence that she directly supported the Royalist cause, unlike her husband and father, and she was given the estate at Coberley with an annual income of £400.

Men serving with the Royalist army did not feel the full effect of Parliamentary sequestration. Many women and children subsisted on only a tiny proportion of the money they had been used to and had to adjust to the new austerity with loss of home and possessions. They had to interact with local and national politicians to try to secure their futures.

Graham Winton, Feb 2025

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the talk given on 14th Nov 2024)

Love and marriage in medieval Oxfordshire.

Rowena E Archer.

14 November 2024

Rowena Archer, a well-known lecturer and medievalist, entertained the audience to some fascinating insights into the issues of love and marriage in the fourteenth century with examples from Oxfordshire and occasionally elsewhere.

She suggested that the surviving evidence – from letters, nearly all of which come from and relate to the nobility, being the literate class –shows that although many marriages were arranged, they were not loveless. And that was despite the fact that issues of wealth, expectations and rank were frequently uppermost in the minds of both parents and guardians when arranging a marriage for a child. Church rules, laid down in Gratian’s Decretum in the 12th century, dominated; the degree of consanguinity permitted, the reading of banns, the marriage ceremony itself and the court, consistory, to which issues post marriage could be brought if an annulment was needed. The contracts issued between the families, detailing the woman’s dowry and any further arrangements were evidence of the legally binding nature of the ceremony, in contrast to clandestine marriages which were frowned on, not least due to the lack of publicity.

Oxfordshire noble, or ennobled families in the 14th and 15th centuries, included the De Veres, the Fiennes and the Chaucers; fortunes varied, much of it dependent on which marriage alliances had been successfully forged. The outstanding example is that of Alice Chaucer whose first two husbands died shortly after marriage and twice left her a wealthy widow, giving her the scope for a third and prestigious marriage with connections to the royal family. Love or concern between a couple is difficult to ascertain from the evidence, although expressions of love are not infrequent in letters; requests to be buried in proximity to a dead spouse suggest affection as do bequests by the husband to the wife of more than the statutory 1/3 of the value of his property. The guesswork required to interpret all the remaining clues to love and marriage is tantalising, and no less for the middle and lower classes for whom practically no evidence of their views survives.

Helen Forde (November 2024)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the talk given on 10th Oct 2024)

Physical attractiveness and the Female Life-cycle in 17th Century England

Dr Tim Reinke-Williams

Dr Tim Reinke-Williams provided us with a fascinating talk on the way in which upper and middling groups of women sought to present themselves in the seventeenth-century.

Dr Reinke-Williams began by pointing out that the seventeenth century was a particularly interesting time to study fashion and physical attractiveness. The opportunity for women, in particular, to cultivate individual fashion experiences became more viable due to two significant factors; changes in English legislation and an expanding global economy. From the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century the country had been subjected to a series of Sumptuary Laws which were enacted to control people’s consumer behaviour. One of the purposes of the laws was to ensure that the class structure was maintained by regulating and re-enforcing social hierarchies through what people were allowed to wear. Furs and velvets, for example, were restricted to the aristocracy. From the beginning of the seventeenth century, however, this legislation lapsed, and without limits on the type of clothing people acquired, both men and women had the opportunity to cultivate their own individual fashionable styles. These new freedoms permeated through to all groups of people; the less well-off simply acquired their clothes second-hand through different routes such as pawn shops, friends and neighbours, employers and even alehouses.

Secondly, an expanding global economy opened up a new range of consumer goods, increasing choice and including textiles and exotic goods from places such as Europe and Asia. The expansion of choice also included a growing range of cosmetic products, carefully promoted as ‘medical’ remedies – for example products to hide blemishes or improve skin tone - which were brought to the customer’s attention through handbills or single sheets, distributed in public places such as market squares and coffee houses.

Unsurprisingly, these developments did not gain universal approval. The middle of the century saw godly protestant reformers targeting the new freedoms of expression by linking them with vices such as drunkenness and sexual immorality. One of the ways this message was relayed was through the publication of cheap, widely available broadside ballad sheets. We were shown a slide of an example in the form of ‘The Invincible Pride of Women’, a narrative verse with a moral warning against the frivolity of middle-class women, condemning those who ‘pillage his Purse’ in frittering away their husbands’ earnings on excessive consumption. However, it is disputed whether these messages of moral correction had the desired effect. For some consumers the distribution of this printed material provided the ideal opportunity for impressionable readers to update themselves on the latest fashionable trends.

On the same theme, we were shown a slide of an interesting painting (artist unknown) held by Compton Verney Art Gallery in Warwickshire entitled ‘Two women wearing cosmetic patches’ (c1655) showing beauty spots on the faces of two women with contrasting skin tones. Both women are seen wearing a conspicuous array of small patches, the message speaking to fears about a perceived increase in moral laxity and anxieties about women’s activities and their bodies.

Finally, we looked at women’s personal writings in the form of letters and diaries to demonstrate how women thought and wrote about their physical appearance across the lifecycle. Attractiveness was important for the female from childhood onwards, not least in relation to competing in the marriage market. However, although good looks gave women social capital, beauty alone was not enough; a good financial standing was equally important. Once married, keeping good looks was believed to help consolidate a relationship. Anxieties could arise, however, when women compared themselves to each other and, for some, to servants perceived to prettier than their mistresses. Although the peak years of beauty were believed to be from adolescence to around thirty years of age, women’s seventeenth-century writings also reveal that the older woman was yet considered to have a beautiful appearance in the later stages of the life-cycle. We ended on a positive note with an example of Margaret Cavendish writing on her mother, Elizabeth Lucas in 1655, whose beauty was ‘... beyond the ruin of time … even to her dying hour’.

This was a most interesting lecture providing insight into how women in the seventeenth century drew on new opportunities to use clothes and cosmetics to identify a sense of self, reflecting on how they wanted to present themselves to society at large.

Rosemary Leadbeater, October 2024

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report of lecture given 12th Sept 2024)

Port Meadow: the 'Boast of Oxford' for a Million Years

By Dr. Graham Harding

Port Meadow comprises 137 ha of flood-plain lying on gravel terraces to the north west of Oxford, bounded to the west by the Thames, and to the east by the raised gravel terraces of the Woodstock and Banbury roads. Through the ages it has seen many different uses from Neanderthal hunting ground, pasture, and recreation to the dumping of rubbish.

Neanderthal stone artefacts have been found on Port Meadow, also Neolithic sites, Bronze Age farmsteads and burial mounds, and Iron Age roundhouses. From Anglo-Saxon times and through the centuries the river has been important for fishing and navigation. By the late 11th century the burgesses of Oxford (known as the 'Portmen'; and later 'Freemen') claimed rights over trade, fishing and grazing which occasioned many disputes with local landowners, religious houses and the University.

Port Meadow has had a number of connections with the monarchy over the years. Rosamund, mistress of King Henry II, retired to nearby Godstow Abbey and died there in 1177. After dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII, legal arguments broke out over the ownership, rights and duties of the Abbey. In 1625 plague drove Charles I out of London to Oxford; victims were housed on 'Port Mead'. When the King’s Oxford Parliament was set up in 1644 prior to the Civil War siege of Oxford, 5000 Royalist horses were pastured on Port Meadow. Later, it was the site of celebrations marking Victoria's Jubilee, and Edward VII's coronation.

Fêtes and pageants were frequent on Port Meadow throughout the years. There were stalls, greasy pole contests, pyrotechnic displays, shooting, fishing, skating (first reported in 1669) bull and bear baiting, cock fighting, wrestling, boxing and many sorts of races (rowing, punting, foot-races, and a long history of horse racing from 1630-1859). In 1760 Winchester played cricket against Eton on Port Meadow (and won), and the game was well established on the Meadow by the early 19th century.

However, not all was good-natured. The Oxford Freemen jealously guarded their fishing and grazing rights with regular infringements leading to pitched battles. Fish numbers dwindled. The regular flooding of the Thames in winter was believed to be integral to its continued fertility. Efforts by Richard Gresswell to 'improve' the Meadow and protect Jericho from flooding were torn down by the Freemen. But the Freemen lost their historic rôle with the Municipal Corporations act of 1835, and their numbers declined from 2000 pre-1850 to 400 by 1902. The final ignominy came when the Council started (1888) dumping rubbish on the Meadow.

Port Meadow was “saved” by WWI. Topsoil was imported and allotments established on the rubbish. Wolvercote Airfield was developed from 1911-1931 and the Royal Flying Corp used it for training in 1912. Captain Barnard’s Air Circus performed regularly, and the Prince of Wales flew in to visit the University in 1933.

Thus the conservative role of the Freemen vanished, although a symbolic ‘drive’ still occurs annually to count the stock and fine interlopers. But Port Meadow is now conserved in other ways, e.g. as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)].

Pamela Wilson, Sept 2024

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Pictures taken at Banbury Fair in Spiceball Park, 15th June 2024)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report by Pamela Wilson of Outing of 23rd May 2024)

Visit to Rousham Park, House and Garden

Thirty nine members of the Banbury Historical Society and friends had a most interesting visit to Rousham House and Garden on 23rd May 2024.

Two informative guides led us on a tour through the house, much of which retains its original features. The original house, situated in rolling countryside between Banbury and Oxford, was built in 1635 by Sir Robert Dormer and is still in the ownership of the same family. William Kent (1685-1748), the well-known architect and designer of landscapes and interiors, added wings and a stable block to the house in the 18 C. His renowned octagonal glass windows were removed in the late 19th century, but are now happily now restored. Many of the original staircases, furniture, pictures, bronzes and some 17th century panelling are still present and were duly admired.

Rousham Park House (and stables) from the bowling green

(For the photos we thank Tim Edmonds)

Thereafter Deborah Hayter, landscape historian and a BHS member, led the group through the superb garden. This renowned estate is characteristic of the first phase of English landscape design and is largely unchanged from its inception. Kent created secret walkways and hidden paths where sudden vistas emerge, punctuated by visions of temples and statues, arcades, cascades and ponds (now bereft of carp owing to the predations of an otter from the nearby Cherwell!).

Rousham Park Gardens – Lower Cascade

(For the photos we thank Tim Edmonds)

The visit ended with a walk round the herbaceous borders and parterre in the walled garden, and a distant glimpse of rare longhorn cattle in the park.

Pamela Wilson

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report by Deborah Hayter of Meeting of 18th April 2024)

Document and Story Session – 18th April 2024

Members had been invited to suggest an interesting document or documents that had a good story that they could tell. We had some really varied ideas put forward, and all the documents had been put together onto one powerpoint presentation so that everyone could see them.

First was Simon Bull who had produced some papers relating to his grandfather who had fought in the First World War in the very early tanks. Simon told us that his grandfather was taken prisoner and had lied to the Germans about his rank because ‘Other Ranks’ were made to work for the enemy. That explained the forged entry in his pay book. He was taken prisoner as part of the first ever tank-to-tank battle when the German advance of early 1918 was stopped at Villers Bretonneux near Amiens.

Then we had Lilian and Walter Stageman who showed some early tax receipts. The story of the discovery of the receipts for payment of the Hearth Tax in the1670s was intriguing: they had been hidden behind a beam in the ceiling of Lilian’s grandparents’ house and one day some plaster fell down and they were discovered. Walter showed us a receipt for ‘Queen Anne’s Bounty’, which was money lent to churches for building works and so on from a fund set up by Queen Anne to help impoverished parishes; also a receipt for the payment of the Poor Rate in 1842 – at that stage each parish was still paying a poor rate for the maintenance of its own poor.

Helen Forde showed a document about one Richard Pack of Flore in Northamptonshire: this was a convoluted tale about a chap who was obviously a bit of a scoundrel.

Philip Gregory gave us a copy of the will of Ethel May Dann, who was the daughter of his Grandfather William Gregory by his first marriage to Annie Elizabeth French who was born in the workhouse. His grandfather lived at 155 Warwick Road opposite the workhouse. Philip also showed the national registration document from when Ethel and her husband Arthur John Dann returned to England in 1916 from abroad and lodged at the Bluebird Hotel. Arthur died in 1917 and Ethel at some time became manageress of the Bluebird. The will had some interesting oddities and a codicil, rescinding some of the legacies in the will, including some money to Philip ‘because he is well off’, (though he was only four at the time).

Verna Wass showed some documents from her father’s naval service during WWII, including his service record written on what seems to be waxed linen. It includes an entry signed by then Captain, later Admiral Sir Philip Vian. Her father was Chief Engine Room Artificer on the Cossack, and was on it when it was sunk, but managed to survive.

Susan Walker had put together a fascinating detective story with a number of excellent slides, all based around a mysterious red diary found in the Shipston Museum. She followed the trail that the diary had started, along the life of the person who had written it, which had taken her in various interesting directions.

Finally Brian Goodey had six items which were definitely ephemera: a beermat from the Essex Brewers; a flyer for the 1993 Fairport Convention Cropredy Festival; a train ticket to the Crystal Palace in 1857; a ticket for livestock travelling on the Great Western Railway; a ticket for coal, being sent from the Betteshanger Colliery in Kent to the Sussex and Dorking Brick Company. These were all interesting as revealing unexpected aspects of the past and Brian wove a great story around them.

Deborah Hayter

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report of Meeting of 14th March 2024)

The Importance of Burton Dassett Southend: combining history and archaeology.

By Chris Dyer Professor emeritus of History at the Centre for Regional and Local History in Leicester.

This was a most illuminating lecture on the medieval market village of Burton Dassett Southend, Warwickshire. Excavation of the site took place between May 1986 and September 1988, prior to construction of the M40 motorway, cutting across the west side of the settlement. Prof Dyer referred to this as the largest and most important excavation in Warwickshire; the most detailed examination of a medieval rural settlement in Warwickshire, if not the West Midlands.

Southend was one of five medieval settlements in Burton Dassett parish.

Unlike the other four, Southend was the site of a market promoted by the manorial lord, with a market charter obtained in 1267. The settlement prospered, became known as Chipping Dassett and approached urban status, but declined throughout the 15thC and depopulated in1497. The only surviving building is the 13thC chapel of St James and adjacent post-medieval Priests House, both elements have been converted into a private house. The main road bisecting the settlement, dividing it into a north and south topography, was named “Newland” and significantly influencing its development and decline; it remains in use today. Excavation of the different properties revealed varying development paths within a process of general community decline against a background of increasing induvial prosperity.

Professor Dyer referred to Southend as an ambiguous place with both rural and urban characteristics including the chapel of St James and a fair on the saint’s day. There were several significant occupations by c1300 including a merchant, mercer, tailor, skinner and cooper but not enough of them for the settlement be a town. In the Northamptonshire Merchants List, c1300, Dassett is referred to as a “town” but at most it can be classed as a proto-town. The “town” plan includes plots of land along “Newland” road which resemble, but are not, burgage plots (characteristically a long and narrow plot of land with a narrow street frontage and outbuildings stretching to the rear of the house or shop in a borough or town). Southend was not a one phase planned settlement. There were earlier structures on the south side of “Newland” possibly dating from the early to mid-13th century with pottery dating to before 1267.

Houses were close together but not continuous and mostly of one storey unlike those to be found in a town. About 25 complete and partial house plans were recorded during excavation, including rebuilding and extensions. The ten excavated tenements, dating from the mid-13thC to late 15thC, included a smithy, alehouse and granary. Professor Dyer referred to all the house plans in Southend as different with a bewildering variety of types but all with a clear link to builder, tenant and landowner. Successive building phases revealed many surviving internal features including a doorjamb inscribed with the name of a tenant family ‘Gormand’ suggesting a degree of functional literacy.

The houses were of good quality construction, primarily using stone foundations with many stone walled up to eaves level. Some roofing materials would have been expensive such as ceramic tiles and stone slates brought from Nuneaton. There was also evidence for good quality carpentry. Adding to the growing evidence that peasant houses were not all poor quality, flimsy structures.

The outbuildings included barns, byre/stables, sheds, a granary, malting kiln and a dog kennel; many were relatively insubstantial or employed more timber than stone in their construction. A number of tools were found during excavation hinting at the daily life and economy of the settlement. Iron tools included an anvil, chisels, reamers, needles and awls. Textile working was presented by wool/flax comb fragments and tenterhooks for drying and stretching cloth after fulling.

The farming regime would have been dictated by the lord of the manor with small tenant farms, based on an open field system producing the ridge and furrow one sees today. The enormous amount of land under cultivation probably reached its maximum around 1300.Charred grains show that wheat, barley, peas and beans were grown suggesting the type of crops grown for consumption not for selling. Animal bone evidence suggests more beef than sheep as eaten by the villagers; eating older animals the younger ones being sent for sale at urban markets.

Evidence for trade included the purchase of building materials, animals and pottery. The latter included Wemsbury ware from Staffordshire with the bulk of pottery coming from Chilvers Coton in North Warwickshire. Also, sophisticated stone mortar dishes and four pilgrim badges including one dating to the mid-14th possibly representing St Peter and St Paul from Westminster.

After the mid-14th century, the tenements show a complex pattern of decline leading to depopulation in 1497 probably caused by enclosure of the open fields and clearance by the owners.

Professor Dyer’s lecture gave an alternative view of viewing an earlier peasant society, its buildings, daily life and economy. Southend was placed in its broader regional setting linking it, for example, to communication routes and trade with urban centres such as Stratford upon Avon, Warwick, Nuneaton, Coventry, and Northampton.

Publications referred to in the lecture:

Burton Dassett Southend, Warwickshire: A medieval market village by Nicholas Palmer and Jonathan Parkhouse. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 44, 2023, published Routledge Oxon. ISBN (paperback) 978-1-032-43001-0.

Warwickshire Grazier and London Skinner 1532-1555 by N.W. Alcock. Oxford university Press 1981.

Peasants Making History: Living in an English Region 1200-1540 by C. Dyer. Oxford University Press 2022.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report of Meeting of 8th February 2024)

"Long Wittenham Anglo-Saxon Hall and the Origins of Wessex"

Dr. Jane Harrison, Field Archeologist and Deputy Director of the 'Origins of Wessex' Project.

Jane Harrison's fascinating lecture dealt with the development of early Anglo-Saxon society in England in the 5th - 7th centuries, primarily focussing on the Thames valley between Dorchester and Sutton Courtenay; the area at the centre of what became Wessex.

A main theme of the talk was the linking of Small-hall Communities with the Great-hall Communities. The Great-hall complex at Dorchester showed many signs of elite occupation, such as noble-metal work and belt-and-buckle remains. The bishopric was founded there as early as 635 A.D. Similarly, the Great-hall Complex at Sutton Courtenay 6 miles upstream to the west, was rich in evidence of manufacture, trade and high-status cemeteries (e.g. at close-by Milton). Half way between Dorchester and Sutton Courtenay, Sonia Hawkes had identified the possible site of another complex, at Long Wittenham. This was subjected to careful investigation by Jane Harrison's team.

Their procedure started with identification of crop-marks, and 'geophysical features' to locate the places to dig, followed by careful excavation of trenches to the depth of 1m. The geophysics was difficult here as the sandy soil gave poor contrast, but rich sites were successfully located. Their major site turned out to be a 'small-hall' ( 11m long, c.f. 30m at Sutton Courtenay). Post-holes, and the lines and dimensions of wall-ditches, were located from the staining of the soil. Doors and hearths similarly. Little was found in the way of floor litter, either because the occupants swept it before leaving (!), or because 13 centuries of ploughing had turned up and removed potential finds from the top 30 cms of soil. Other characteristic building were 'round-houses' and 'sunken-feature building', now interpreted as storage sheds and places for spinning and weaving. The small size of the hall ruled out 'royal' occupation, and suggested the rise of powerful citizens of intermediate status.

The interpretation of the finds was enormously aided by the extensive experience the team had acquired in other early Anglo-Saxon sites in other parts of Britain. Jane Harrison showed us similar finds made at Yeavering in north Northumberland, where a Great-hall complex was investigated, and a lesser hall complex at nearby Thirlings. Also linked.

Another early small-hall site was described in a loop of the Thirston Burn near Felton, also in Northumberland. Here we saw a fascinating detail, for in one of the sunken-feature buildings a large array of loom-weights was found so aligned as to suggest that the vertical-loom together with the incomplete cloth and indeed the hut itself had been burned, so that the weights all fell together to lie undisturbed for 13 C. Another intriguing detail was finding a fatty mass in one of the weaving houses. It was suggested that the fat was used for water-proofing the cloth.

Returning to the idea of linking, it was suggested that a local king could travel round from one Great-Hall to another moving when he had exhausted the hospitality of his hosts. The eventual kingdom of Wessex arose by the coalescence of many of these smaller communities around the 'royal' centre of Dorchester.

Ian West, 10th Feb. 2024

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report of Meeting 11th January 2024)

“The Personal History of Shoes” : Professor Matthew McCormack

Prof McCormack is Professor of History at the University of Northampton. He has appeared on TV and radio and has published widely on British history, his most recent book being “Citizenship and Gender in Britain 1688-1928”. He is currently writing a book called “Shoes and the Georgian Man”.

Matthew started his lecture by observing that shoes are very personal objects. They support the wearer’s weight but may also reflect their job, their style and project an image of the wearer. Thereafter his lecture encompassed 5 main themes :

Historically at the beginning of the 18th century men and women’s shoes were quite similar, although men favoured stacked heels to promote height – equated with high status, horse riding etc – while women’s shoes usually had waisted heels. Indoor shoes were often of silk with a brocade cover. Thereafter styles diverged until by Regency times black leather boots were popular for men while women wore more delicate styles in silk or wool.

The second theme focused upon the intimate relationship between shoe and wearer. Traditional leather shoes moulded to the foot, becoming more flexible over time yet hard-wearing. New shoes were made by a cordwainer while a cobbler mended them ; second-hand shoes denoted low social status (and it was thought they could transmit disease!) although later in the 18th century when shoes became very expensive they became more acceptable.

The third theme considered what shoes tell us about the wearer, that is the shape of the foot, the walking gait, what they were used for and even whether they had traces of body fluids such as sweat or blood which could be used for DNA analysis. A consignment of shoes aboard the sunken HMS Invincible at Chatham Dockyard provided many insights, including the extra-wide shoes fashioned for gout sufferers.

Shoes may represent the wearer. An 18th and 19th century practice was to conceal a shoe near a threshold or door or up a chimney, to protect against evil spirits.

Shoes may tell a story. The method of manufacture has changed little since the late 19th century, and Northampton shoemakers such as Trickers have a longstanding reputation for quality (and expense) ; they are the predominant companies in London’s Jermyn Street. Prof McCormack demonstrated his own shoes made by Trickers! Thus shoes may be viewed as primary sources, and traditional methods are still used today by suppliers for historical re-enactment and the theatre. The first stage of manufacture involved ‘clicking’, i.e. cutting out the shoe shape from a leather sheet, a most prestigious occupation. The shoe came with 2 long straps and a buckle, bought separately : on first wear, a hole in the strap was made to attach the buckle. The same ‘last’ was used for both left and right and the shoes worn until they became comfortable after 2 weeks or so. In time modifications such as hobnails on the front and horse shoe nails on the back were made for soldiers’ shoes.

Following on from the recent discovery of the oldest shoe known in Britain, a Bronze Age shoe found in the Thames estuary, this was altogether a fascinating lecture.

Pamela Wilson, 13 Jan. 2023

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the lecture by Debora Hayter of 14 December 2023

How enclosure shaped Oxfordshire’s landscape

Deborah Hayter 14 December 2023

Deborah Hayter suggested that her lecture could be subtitled ‘How common rights became private property’. To demonstrate how the landscape changed over the course of 300 years she cited the contrasting estimate of Gregory King in 1690 and the findings of the Royal commission on Land in the mid-1950s. In the late 17th century King suggested that 25-30% of the land in England was Common (or 8-9 million acres), whereas in the mid-20th century only 4000 commons were recorded with an acreage of 1 - 1.3 million acres, many of which were situated in the upland Celtic fringes and the north west.

She posed the question as to whom the common land belonged? (Always to someone, or to a group of people.) And the nature of the common rights? (Personal to a household, and could include grazing or fishing, turbary (right to cut turf or peat for fuel) or the right to collect wood for fuel.) But external circumstances in the Middle Ages, such as changes in the weather pattern (e.g. the difference between the relatively prosperous 13th century and the harsher climate of the following 100 years), the effects of widespread plague (e.g. the depopulation caused by the mid-14th century Black Death) and changes in international trade could separately or together result in movement towards the enclosure of land by private owners and the consequent loss of individual rights by a large fraction of the population.

Enclosure was not always acrimonious. It could result from an agreement between land owners and a parish about enclosure and in the 16th and 17th centuries such documents, enrolled in Chancery, are testament to good working relationships.

By the 18th century however, changes in agricultural practices, such as improved rotation of crops, and the additional land available for agriculture to feed a growing population as a result of improved drainage systems led to increasing enclosure and diminution of common rights. Not all parishes were the same, but in many parishes the owners of 75% of the land had to agree any enclosure - even if this was a single large landowner. Nor did enclosure happen by the same legal process in all parishes. But as a result, the landscape changed with straight roads of uniform width being built, hedged fields being created in rectangular shapes no longer following old boundaries, new farmhouses being built away from the villages to house the tenant farmers, and forests -such as Wychwood - being largely destroyed. A general 'Inclosure Consolidation Act' was passed in 1801 which really spelt the end of common rights, as more parliamentary enclosure took place throughout the first half of the 19th century. In the East Midlands Oxfordshire was the epicentre of enclosing activity and, as elsewhere, the county suffered from the consequent poverty of agricultural labourers, no longer able to access old rights. The result was rural depopulation as workers headed to towns and cities for work, or even emigrated.

So, the landscape has changed radically from 500 years ago, as has also the occupations of those rural communities which had existed in the same way for previous centuries. The extinction of their common rights has had far reaching, and probably unforeseen consequences.

Helen Forde (December 2023)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the lecture of 9th November 2023 by Dr. Alan Crosby)

‘Truth is stranger than fiction’: the extraordinary life of

Marjorie Crosby Slomczynska (born Banbury 1884)

Other people’s family history can be a little tedious, but few people have such a colourful figure in their family tree with such an unexpectedly racy life to explore and relate. Alan Crosby’s great-aunt Marjorie was born in 1885 into a respectable middle-class Banbury family, but obviously finding English life too humdrum went to Hamburg and found herself a Russian ‘protector’, whom she accompanied to St. Petersburg, where there was a large English community and English women were much admired. She appeared to have lived a high life there, but is next found near Dublin in 1906 where she gave birth to her first child. It seems that she had returned to Russia, and there was another child in 1910; in 1912 she married a Polish sports journalist. The advent of the first World War and the Russian revolution meant that Russia was in turmoil and very unsafe, and in 1918 she escaped to Warsaw, still then in the Russian Empire, where she met Josef Pilsudski, a Polish hero, the first chief of state (1918 – 1922) of the newly independent Poland. At this stage there is a photograph of Marjorie who was working as a secretary in the small British Legation in Warsaw. In 1920 the Russians invaded Poland but were beaten off largely with the help of the Koscuchkov squadron, which mainly consisted of American mercenaries. Marjorie fell in love with one of them, called Merian Cooper, and had another child by him, though eventually he returned to the USA without her. At some stage Marjorie became an Irish citizen, helpful when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. In 1944 the Warsaw Rising took place and Warsaw was destroyed in return: the whole city was evacuated and 650,000 people displaced. It is thought that about 50,000 Poles died in transit to the camps they were sent to. Marjorie survived and lived out the rest of her life in Poland. Alan had managed to find and make contact with some of his Polish cousins and had visited his great-aunt’s grave. Truly an extraordinary life and a well-researched and well-told story.

Deborah Hayter (November 2023)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the Lecture of 12 Oct 2023)

The Battle of Middleton Cheney, 1643 – by Gregg Archer

Many members may have been surprised to see the title of this talk in this years lecture programme as this Civil War engagement has traditionally received little attention in the annals of the wars which ravaged these islands in the mid seventeenth century. So, it was a capacity audience that gathered at Banbury Museum to hear Gregg Archer, of the Mercia Region of the Battlefield Trust, present a detailed account of his researches into what actually happened on the outskirts of Banbury on May 6th 1643.

A summary of the causes of the wars set the context and introduced the key players. In the aftermath of the Battle of Edgehill, of the taking and garrisoning of Banbury for the King, and his establishment of Oxford as his Capital, everything was set for Banbury and it’s hinterland, and the whole Midland region, to be centre stage in the unfolding conflict. The crisscrossing of the area by Parliamentary troops attempting to take back key garrisons such as Litchfield and Stafford, combined with the 'fake news' promulgated by both sides in attempts to trick their opponents into traps, led to something of a febrile atmosphere in the area in late 1642 and the early months of 1643. In this climate it is unsurprising that reports reaching Parliamentary forces in Northampton, that Banbury town had been put to fire by Royalists, provoked public outcry in late April 1643.

To what extent they were motivated by revenge, or an opportunistic hope that in the ensuing chaos Banbury Castle would be easy pickings, is unclear. However the beginning of May saw Parliamentary troops from Northampton on the move to take Banbury by stealth, unaware that powerful Royalist cavalry forces were already massing there to protect a munition shipment, sent by the Queen from Newark to Oxford, via Banbury.

After a rendez-vous at Culworth, the Parliamentarians set off to skirt Banbury to the south east crossing the Cherwell at Bodicote ford to mount a surprise attack, avoiding the well defended Banbury bridge. However the surprise was on them when, approaching the ford, they were greeted by a large force of Royalist cavalry, alerted by intelligence from Culworth, strung out along the ridge beyond.

Discretion prevailed over valour and they retraced their steps, followed by the Royalist cavalry who sent a harrying party ahead to slow down the retreat to allow their main force to cross the ford in pursuit.

On reaching the outskirts of Middleton Cheney the forces of Parliament, mainly infantry, turned and faced their opponents, making use of a ridge of land to mount a defence. The opposing cavalry formed up to face them. Battle commenced with a Royalist cavalry charge on each flank at which point, in the words of Parliamentary reports “all our horse ran away”. This left the infantry exposed but, after firing one volley and before they could reload, a second cavalry charge fell upon them and, again in the words of Parliamentary reports, “every man shifted for himself”. The whole engagement lasted no more than half an hour.

Scattered forces of Parliament made their way back to Northampton and the Royalist cavalry returned to Banbury with a significant load of captured muskets and prisoners.

The two sides gave conflicting accounts of the numbers killed and injured. However given the brevity of the encounter, and that no more than five hundred or so were engaged on each side, the 47 registered as buried in Middleton Cheney, and the 5 or 6 in Banbury seem to give a realistic indication.

Gregg’s researches are meticulous and detailed, drawing on a wide range of primary sources. He has balanced the sometimes dubious reliability of contemporary accounts, cross checking details and balancing for possible bias. This was all presented in a clear and coherent narrative, well supported with visual material, which engaged the audience and I suspect provoked their interest to know more. (By coincidence there is a book available: The Battle of Middleton Cheney 6th May 1643 by Gregg Archer, published (2023) by The Northamptonshire Battlefields Society, ISBN 9798849687179 .)

In terms of placing this engagement in the overall balance of the conflict as a whole, Gregg was clear that it had little impact on further events. While technically a battle, defined as an encounter where both sides form up before engaging, it formed no part in any coherent plan and was predominantly reactive and opportunistic in character.

Verna Wass, 14 Oct 2023

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the Lecture of Thursday 14th Sep 2023 )

The Life of a GP in Banbury in the 1960s – by Sir Roy Meadow

In the first lecture of our new autumn series Professor Sir Roy Meadow gave us an interesting and personal account of his life as a General Practitioner in Banbury in the early 1960s. As his first full-time appointment, it provided him with many still-vivid memories of his experiences as a junior partner in the West Bar practice.

We learnt that Prof. Meadow’s training took seven years, as it does today; 3 in Oxford followed by 3 years clinical training at Guy’s hospital, plus one year’s pre-registration training. Even at a time of no tuition fees, only four per cent of school leavers in the 1960s went to university [compared to around approximately 37 per cent in 2022]. The gender balance was also very different at that time. To illustrate, the audience was shown two photographs of resident first year doctors, one from the 1960s and the second of the present day. In the former, 25 out of 28 doctors were men, (all attired in three-piece suits), whereas today over half of medical students are women.

In the 1960s Banbury was fortunate in having a doctors’ practice well-known for its high reputation. At a time when most practices contained only one or two doctors, West Bar surgery was among a very small minority of practices employing five trained medics. This is surprising as work in general practice was not especially popular; the ‘specialist’ work of a hospital consultant was considered superior.

West Bar surgery was built in 1871. The ground floor comprised an operating theatre, testing centre and fracture room plus areas for dispensing. The surgery also had a garden. The second floor contained the doctors’ accommodation. Ninety per cent of patients were treated under the NHS and ten per cent privately. This division was apparent as soon as the patient entered the building; private patients turned to the left and NHS to the right. Surgeries were held twice a day and the partners also ran clinics at outreach centres such as those at Middleton Cheney, Bloxham, Adderbury, in local schools and at the Alcan Aluminium Works in Banbury [built in 1930 on Southam Road, closing in 2008]. Atypically, the surgery was also linked with Horton Hospital (also built in 1871) where West Bar GP partners carried out duties in the radiology department among others. Back at West Bar, junior doctors had additional duties, such as answering the door (which was manned 24 hours a day) when the reception staff were not there. Perhaps one of the most entertaining of a doctor’s jobs was to judge babies at local shows (alongside vegetables!).

In the 1960s most patients’ medical encounters were with their general practitioner. Only ten per cent were seen in hospital and these visits were mainly for tests or X-ray services. A major part of a doctor’s work involved home visiting, if necessary over a wide area from Boddington in the north to North Aston to the south. Night calls were a feature of general practice although patients did try to avoid contacting a doctor in the middle of the night, making a 7.30 am call to the surgery particularly worrying, as patient may have ‘held out’ until the end of the night before telephoning.

As most mothers had their children at home in the 1960s, home visits often involved delivering babies and the audience listened to a couple of brief vignettes of some of these (usually happy and rewarding) cases. A striking feature of Professor Meadow’s home visits was the kindness and decency of people in their homes, many of which did not always have the luxuries of electricity and hot water that we enjoy today.

Professor Meadows concluded on a positive note; his time in Banbury is remembered with vividness and warmth, allowing us to reflect on general practice in Banbury over 60 years ago.

Rosemary Leadbeater. September 2023

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the Outing of Thursday 29th June 2023)

A Walk through St.Thomas’ district of Oxford 29:VI:2023

With map and historical images in hand the fifteen BHS members followed Liz Woolley over the streets of St Thomas’ neighbourhood in Oxford. So close to Oxford’s heart, yet historically a place to avoid, and today a dense reconstructed district just off the axis between rail station and the Castle.

(The starting point...within the enclosure of Oxford Prison turned hotel.)

Several themes intertwined with the paths we took and the waterways we crossed. Early extra-mural milling, malting and brewing along unobtrusive streams, a continuity through to the late 20th century. A working class and lodging community, tight knit, between rail arrival and city fringe employment. Poor backland housing on Christ Church College land, redeemed with experimental Prince Albert inspired model housing that survived the slum clearances of the mid 20th century.

Today an enticing tangle of roads and passages, with many brick-and-gate-defended new opportunities, but sufficient of the past to catch the enquiring eye. To think that undergraduates Morris and Burne Jones risked the ‘town’ to reach St Thomas church for worship.

(The Swan Malthouse of c. 1830, part of a largely hidden Oxford.)

Liz Woolley was an excellent guide both background and personalities to retrieve the soul of a place which might otherwise seem to be an over-polished series of apartment investment opportunities.

Brian Goodey, 1st July 2023

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the Outing of Tuesday 6th June 2023)

Outing to Bloxham Museum and St Mary’s Church

(Based on an account by one of our members, Cliff Baughen - thank you Cliff.)

On Tuesday 6th June Banbury Historical Society organised an ‘Outing’ to Bloxham Museum and St Mary’s church (which is practically next door).

We visited the Museum first. It is small with basically one room for the displays. On previous visits there had been a ‘Baughen Bible’ on display but it was not there on Tuesday. There was an article on William Herbert Baughan with photos of him and his wife. He was the first Railway Station Master of Bloxham Station. One of the…children, Fanny Baughan (married John Hooper), had a daughter, Barbara (married name Brown), who was an authoress. Her books included one on the local railway line. It is worth visiting….but please check opening times and dates as these are limited (run by helpful volunteers). Parking is limited. (Photo courtesy of Cliff Baughen)

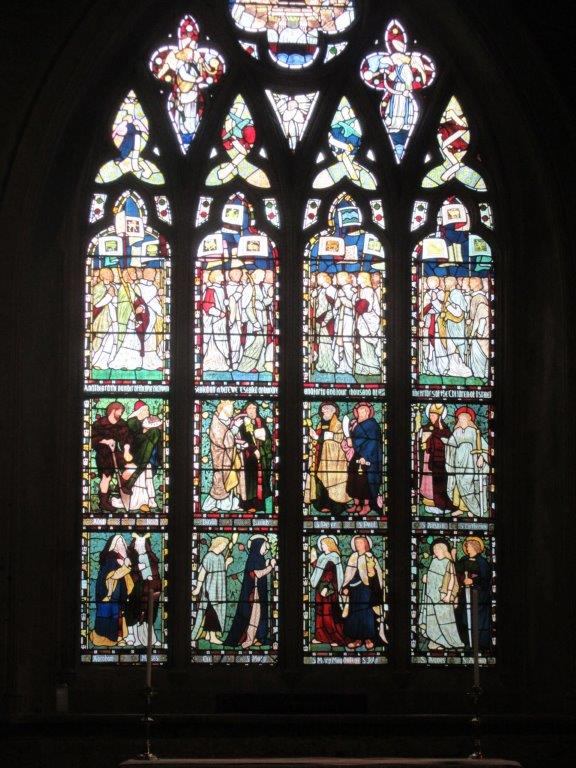

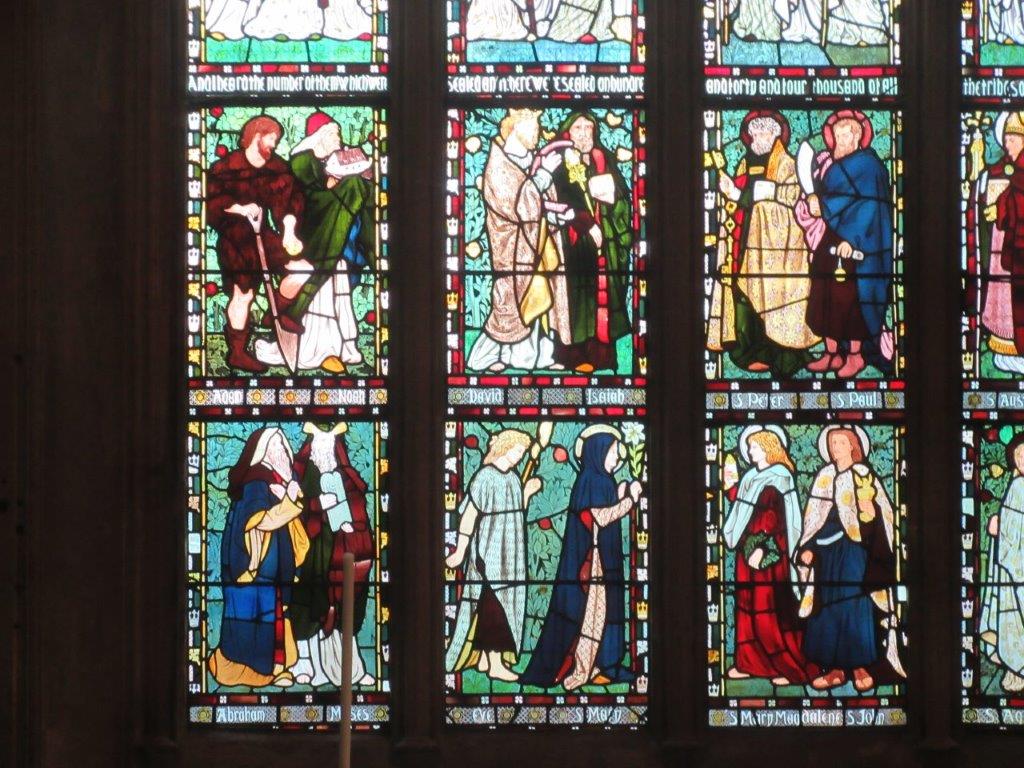

St Mary’s has been the site of a church from at least the Norman times. It is the only Grade 1 buildings in Bloxham. It is build of local stone by local hands, and has N & S aisles of unusual width. The spire is the tallest in Oxfordshire and rises to 198 feet. (For an excellent guide to the church see: https://www.stmarysbloxham.org.uk/historyofstmarys.htm)

We had 2 excellent guides (from the St Mary’s Bloxham Heritage Group) who showed us around the church and churchyard in two groups. The weather was rather on the chilly side but that did not stop people going on the tour of the outside. Our guide pointed out the various architectural features including the distinctive North Oxfordshire style of detailed (if ‘garrulous’) decoration. He also showed some gravestones of some ‘residents’. For example, there was the teacher from Bloxham School who died of a cricketing injury; he broke a bone which turned septic.

One very interesting point was the Pest House Drive, now grown over, but clearly marked (direct from Pest House to graveyard, to avoid contagion.)

Inside the church there is plenty to see. In earlier times there were wall paintings, later plastered over. Many of the paintings were lost during the removal of the plaster but at least one survived.

The paintings on the chancel were vandalised, presumably by Parliamentarians in the Civil War (1642 – 1652). The church has a number of notable glass windows. The ‘East’ window was designed by Victorians William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. The church has many stone carvings inside and outside; some headless. (Photo courtesy of Tim Edmonds.)

There is only 1 large decorative tomb (Sir John Thornycroft – 1745) in the church reflecting the relative absence of stately homes in the manor. Many tombs on the floor inside the church were covered up by Victorian tiling.

We had a very enjoyable evening and it was well worth making the journey from Reigate.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Banbury Historical Society - Stratford Upon Avon Visit 2023

Recent analysis of 15th-century wall paintings in Stratford’s historic guildhall has led to a reinterpretation of their probable date and the purpose behind their creation. The BHS enjoyed an illuminating tour of the guildhall by Lindsey Armstrong, General Manager of Shakespeare’s Schoolroom and Guildhall, which included a special viewing of the recently found and restored wall paintings. The tour concluded with a fascinating step back into 16th education in the schoolroom where the young William Shakespeare was taught.

Stratford Guildhall and Chapel

In the late 13th century, the Guild of the Holy Cross received permission to build a chapel and hospital in Stratford-upon-Avon. In 1403 the Guild amalgamated with those of Our Lady and St John Baptist. Adjoining the chapel is the timber framed 1417/1420 Grammar School, originally the Guildhall, associated with John Shakespeare and his son William, and 1427 almshouses.

Over time the guildhall was adorned with elaborate wall-paintings depicting scenes of the Day of Judgement, the deeds of saints and the life of Adam. However, from 1553 with the suppression of religious guilds, the guildhall housed the Stratford Borough Council and the popish images ordered to be removed. Luckily, their “destruction” was limited to a covering of whitewash until some were rediscovered in the 19th century. In 2016 during conservation work undertaken when the guildhall was to open to the public for the first time, traces of the once colourful wall paintings were uncovered.

In the priest's chapel, on the ground floor of the guildhall, a triptych painted directly onto plaster over the alter, showed God the Father cradling a crucified Christ, with figures of the Virgin Mary and St john the Evangelist on either side. The major discovery, painted onto one of the wall timbers was a well-preserved image of John the Baptist. Research suggests the alter paintings might be as early as the 1420s.

The former guild refectory, then Master’s Chamber, on the first floor was also decorated with once colourful wall paintings, which for centuries had been covered by book cases. When removed, the traces of 13 alternating red and white striped paintings were found, each topped with a shield in a contrasting colour. Once thought to be heraldic shields research now shows them to be 13 portrait busts of Christ and the Apostles, originally (probably) a mural of the Last Supper set within the guild refectory. Also in the room was the painting of a Marian rose, a symbol used in the very early 15th century dedicated to the Virgin Mary, one of the principal dedicatory saints of the guildhall.

Full details of the reinterpretation of the guildhall paintings can be found in the March 2022 edition of Current Archaeology. The Guildhall and Schoolroom is open to the public; for details, visit www.shakespearesschoolroom.org.

GW July 2023

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the lecture of Thursday 9th Mar 2023)

‘Rememorative or minding signs or tokens’; images in parish churches before the Reformation

Elinor Townsend, 9 March 2023

This lively and well-illustrated talk demonstrated above all how richly decorated medieval parish churches were and reminded the audience of the purpose of many of the colourful images, in stone, wood, glass, textiles and paint. Each was intended to encourage prayer for the souls of the departed and consequently to reduce their stay in purgatory. Evidence for the earlier abundance of images is still obvious with empty niches, fragments of glass, re-ordered rood screens and damaged monuments, but also surviving personal tombs, recovered wall paintings and repaired vestments.

Elinor Townsend cited five different categories of images which were destroyed or damaged in the 16th century – particularly paintings which were intended to be very visible to the laity, confined to the body of the church and unable to see the priests in the chancel, other than when the host was raised at Easter. These included pictures of Christ or saints on rood screens and Doom wall paintings above the chancel. Many were painted over at the Reformation only to emerge later.

Secondly, images which contravened the ten commandments were damaged, many of which were stone or alabaster altar pieces. These were not only behind the main altar but might be found in multiple locations within churches; side chapels frequently had altars or tables, places which increased the opportunities for redemptive prayer. Local examples include the Somerton altar piece, now returned to the church though much restored. Similarly other individual wooden, stone or painted statues were damaged or removed – these had been installed in places where prayers could be said, or might have decorated surfaces in the church, contributing to the busy – and probably noisy – atmosphere.

A third category of image included those that provided a narrative, usually of the life of Christ or the saints; wall paintings were frequently whitewashed over to avoid penalties from the inspectors of churches after the Reformation but in some cases have re-emerged due to subsequent repairs or investigations, those at South Newington being nationally noteworthy. Fourthly, decorative images such as the wall paintings at Bloxham, and masonry, both inside and outside the fabric which frequently depicted figures or mythical beasts; good examples of such work by a north Oxfordshire school of masons can be found in the churches at Hanwell and Bloxham where linked arms are carved at the top of columns. The few remaining church vestments from before the Reformation demonstrate the importance of the images embroidered on the back of the clothing of the clergy, visible to the laity but very vulnerable due to the fragility of textiles. Only a few survive despite the calculation that every parish must have owned six to eight copes but the fragments of the well-known cope at Steeple Aston indicate the quality of needlework which could be found even outside the capital.

The final category, commemorative images also suffered damage over the centuries but less than the relics perceived as holy; recumbent figures frequently included a request for prayers in the inscriptions but were intended for ostentation as well as commemoration. Highly coloured, they would have added to the general decoration of the church, very different from the sombre interiors found today.

In conclusion it was noted that not all damage was due to deliberate acts; decay, neglect and accidental damage have all resulted in the loss of monuments as well as the Puritanical zeal in the post Reformation era, the lack of interest in medieval material in the 18th century and the Victorian passion to beautify churches in their own style. In the 21st century churches and their contents are threatened by the cost of maintaining them and reduced congregations; supporting them through historic churches trusts ensures their survival for further centuries.

Helen Forde (March 2023)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on the lecture of Thursday 9th Feb 2023)

Revising Pevsner’s Oxfordshire, by Simon Bradley

Like the editors of cricket’s annual 'Wisden', Dr Bradley’s name will doubtless never displace that of the originator of 'Pevsner's Architectural Guides' the national county-by-county survey of significant architecture.

Sir Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83), son of a Russian Jewish fur trader, was a rising art historian when, in pre-war Germany, his origins forced him to move to England. He brought with him a rigor, a persistence, and a new perspective on English art. With curiously right-wing views, he was nevertheless appointed to Birkbeck College, London and was embraced by the expanding Penguin publishing house. He edited the still attractive (and now highly collectible) 'King Penguin' series.

The name 'Pevsner' will forever be remembered by architectural professionals and the informed public for the 'Buildings of England' series of bulky gazetteer manuals which began, with those of 'Cornwall' and 'Nottinghamshire', in 1951. But county boundaries change, buildings have come and gone, and research is continually bringing to light more information. The Guides for some counties are into their fourth editions.

Dr Bradley of St John’s College, Oxford is in the process of revising part of the 1974 ‘Oxfordshire' guide, which has been divided into two volumes. In a well illustrated and engaging account, he discussed 'Oxford and South-East Oxfordshire', a territory dominated by Oxford city but including substantial additions from Berkshire since 1974,

Pevsner’s original 'Guides' were based on initial research notes by assistants, followed by extensive and probing tours of every parish, and subsequent correspondence with national specialists and local experts. Although research media, access and attitudes have changed over seventy years, today’s revision process seems very similar.

The purpose of the new edition is to "correct, update, expand and enhance" each parish’s entries. Bradley illustrated this by showing the original and revised texts for Blomfield’s 1910 suburban All Souls church in New Headington, Oxford. (Pevsner’s compliment on the impressive interior was retained; impressive new glass added.)

This spirit-lifting space, from the Reign of George V, was in contrast to St Katherine’s church, Chiselhampton, a village equidistant between Oxford and Wallingford. This ‘boutique’ church, with box pews and west-gallery, redundant since 1977 and now promoted as a ‘champing’ (i.e. church-camping) venue, was re-built in 1762-3 by Charles Peers, a new-money Lord of the Manor. Its Georgian simplicity still posed many questions as to date and sequence. Interestingly a 20th century successor to Peers was Sir Charles Reeve Peers (1868-1952) an architect who, in 1910, became England’s second Inspector of Ancient Monuments and from 1913-33 was Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments.

Following several further observations on individual sites, access and attitudes, the speaker was open for questions and comments. Pevsner’s contacts with W.G. Hoskins, whether sites could be over-researched, changing architectural preference, and the basis of qualitative value judgements were all raised. Could it be said of Pevsner that he did more than record the artefacts; he established an aesthetic?

Brian Goodey, Feb 2023

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on lecture of Thursday 12th Jan. 2023)

HS2 Excavation at "Blackgrounds", Chipping Warden: Report on lecture by James West.

The HS2 project has hastened the identification of many archaeological sites along its route from London to Birmingham. One of these close to Banbury, at "Blackgrounds" farm (so named because of the dark soil overlying the settlement layers), has excited great interest because of its long period of occupation – over 1000 years from c.700BC to 400AD. Such a site, involving successive generations of apparently cooperative settlement – a so-called ‘conglomerate’ site – is rare in Northants, indeed only three are known.

James West, the Site Director of this excavation at Blackgrounds told us that, during the entire 14-month excavation period, 60 – 80 archaeologists were employed onsite by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA). Seven areas of archaeological potential were identified, in the north, central and eastern sectors, which were then subjected to geophysics and trial trenching.

Artefacts in the north sector were found to be predominantly Iron Age in origin, although investigation here was impeded by deep-seated 'ridge-and-furrow'. Many C-shaped enclosures were found, as well as hundreds of pits used for storage and deposition of unwanted material, and post holes denoting fence lines, domestic structures and 4-posters used for grain storage. A large Iron Age droveway was discovered, 2-3m wide, used as a transport link right through the site in a NW direction. The northern network of pits, enclosures, etc., was thought to be involved in animal husbandry and butchery, with remains of smelting and metalworking at its lower margins. The largest roundhouse on the site, containing a smaller private internal area (probably the dwelling of the ‘big chief’), was found here. However, most of the 30 or so Iron Age roundhouses were in the eastern sector; these appeared about 700 BC and showed evidence of successive re-fashioning over the centuries.

The central and southern sectors showed predominantly 3rd-4th century Roman activity although it probably commenced earlier, in the 1st-2nd centuries. Only 15% of the Roman settlement area was excavated as it was very extensive. After AD43, when the Romans arrived in Britain, there was no abrupt change at Blackgrounds in style of pottery or housing, etc., confirming the cooperative nature of the transition. Previously, in 1830, a separate Roman villa-complex had been identified to the west of the Blackgrounds site ; it was not explored during this project but a 6-10m wide Roman road was found travelling E-W and probably connecting with this villa. Various pathways led off this road into the settlement, and the Iron Age droveway was also metalled at that time. The water level of the nearby River Cherwell was known to be higher in Roman times so it is possible that boats could approach in this way. A stone latrine and cistern were found next to the road. Roman-style domestic buildings often incorporated an Iron Age clay floor, overlaid with a footprint of smaller herringboned stones, then a surrounding wall of clay-bonded larger stones to chest height with a timber superstructure.

Part of the Roman sector was demarcated for industrial use with multifunctional stone and clay-lined kilns for smelting, bread making and pottery, and beautifully preserved wells. 3 tons of animal bone were found and 1.3 tons of pottery, as well as 800 coins and 1200 iron nails. Many loom weights, querns, scale weights, scale bars, styluses, glass vessels, a leather-punch and even a shackle were uncovered. The coins ranged from crude Iron Age examples to specimens in copper or silver from all across Europe, including many British copies. Jewellery finds included an Iron Age jet bead, snake’s head bracelet and Saxon brooch pin (found on the surface), as well as beauty products such as combs and tweezers. Some very rare shale pottery was found, and decorated Samian ware – high-status pottery from Gaul.

Some 20-30 cremations were found, as well as 17 adult and 15 infant burials. No unifying feature could be discerned – some upside down, some partial, some headless. Most were in the pre-Roman Iron Age or post-Roman Saxon areas.

From the wealth of the finds, the longevity of the settlement and the highly productive activities evidenced, we can deduce that Blackgrounds was a most significant trading centre in Roman times. It was abandoned in 410 AD. The village of Chipping Warden is known to be of Saxon origin and was established nearby at a separate site.

Pamela Wilson (Jan. 2023)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

(Report on lecture of Thursday 8th Dec. 2022)

‘The night-time haven of the wandering tribes’: the common lodging-house in Victorian England, by Liz Woolley

Liz Woolley presented a comprehensive account of the workings of the common lodging-house, focussing especially on Oxford and Banbury. We were guided through details on how common lodging houses arose, the sites and buildings they occupied, what life was like for the occupants and keepers, why and how local communities attempted to control their use and reasons for their decline.

Common lodging-houses were in existence from the early eighteenth century onwards. By the nineteenth century they were a well-established form of working-class accommodation, with an ever-rising demand associated with factors such as urbanisation, Irish immigration and an increasing separation of work and leisure activities. Locally, some common lodging houses remained in existence for up to 100 years, thereby becoming a familiar feature of the Oxfordshire landscape.